The Boston Branch of the NAACP has quietly made a departure from the longstanding position of most of the city’s Black leadership on affordable housing. The NAACP’s new approach is a refreshing and insightful addition to the standard approach.

Going back to at least the 1960s, Black leaders and community organizers have called for the construction of more affordable housing. The Banner reported on these demands and pleas in the early years of the newspaper’s publication.

Over the decades, city government officials have responded, with varying degrees of vigor, to the demands to make it possible for more residents to afford the basic human need for shelter.

By 2021, 54% of the housing units in Roxbury were income-restricted, the highest level of any neighborhood, according to a city report. Citywide, such housing was most often restricted to occupants earning less than half of the area median income, one way of defining affordable housing.

In Dorchester and Mattapan, the proportion of income-restricted units was 19%, matching the citywide level. Vast majority of Black residents of Boston live in Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan.

The income-restricted units the city inventoried include public housing, private units constructed with government subsidies and one built under the city’s inclusionary development policy.

Yet there remains a need and appropriate demand for more affordable housing. The city and developers just can’t build enough of it fast enough to meet the demand, which city housing chief Sheila Dillon acknowledged more than a decade ago. Since then, the shortfall has been exacerbated by the rising cost of construction materials.

After 60 years or more of advocacy and official action, it should be apparent that building more affordable housing alone won’t get the job done.

The new leaders of Boston NAACP are adding another, less direct approach that defines the housing problem for Black residents in a different way. The argument is Black workers need higher incomes so they can afford housing at market rates.

Here’s how Rufus Faulk, vice president of the Boston branch, put it to the Banner’s Avery Bleichfeld last month: “I think, oftentimes, when we think about housing, we think about it strictly around this lens of affordable housing. But a portion of this also has to be, how are we making sure that Boston’s Black residents, Black population, are able to earn a living wage or be able to increase their earning potential so that they can withstand any rises or dips in the housing market?”

Faulk said the branch would collaborate with existing programs to bring more residents of color into the emerging life sciences and climate tech industries or hospitality as tourism bounces back from the pandemic. With the latter, the focus ought to be on increasing the ranks of hotel managers and other executives.

“We’re not going to be able to be all things, but we want to make sure in our partnership spaces, we are partnering with organizations and individuals who are in the space of doing this work,” Faulk told the Banner.

Before Faulk and the Boston NAACP, a few scattered voices have called for broadening the single-minded approach to affordable housing.

When he was directing the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative more than a decade ago, Curtis Jones once cited the need to raise incomes so more people of color could afford market housing.

In 2022, then-City Councilor Tania Fernandes-Anderson created a stir by calling for a moratorium on affordable housing in Roxbury because of the concentration of such units there. She called for spreading them around the city more.

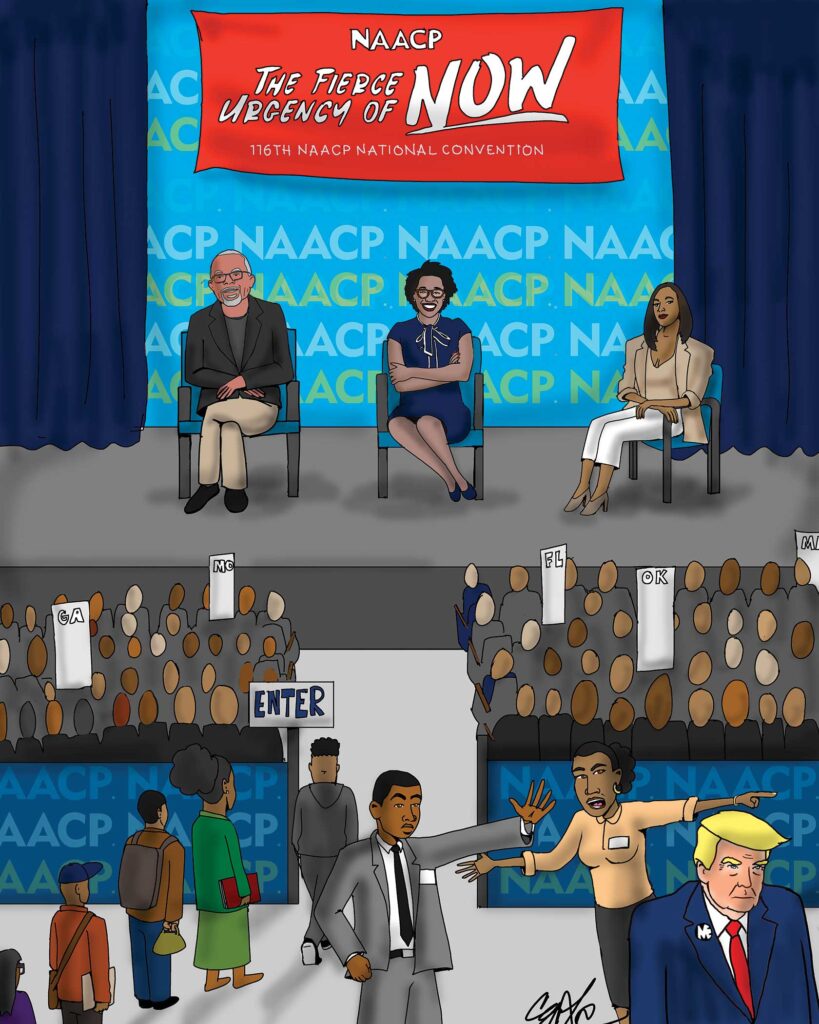

Faulk disclosed the Boston branch’s new income-based thrust on housing not long before the NAACP held its national convention in Charlotte, North Carolina, during the second week of July. Here’s hoping Faulk and Royal Smith, president of the Boston branch, shared its new direction with other delegates. It’s worthy of adoption by other branches and, indeed, the national civil rights organization.

The convention, to which the sitting U.S. president wasn’t invited for the first time in the NAACP’s history, featured a keynote speaker who focused on health equity and a panel of the Congressional Black Caucus members discuss ing political strategy. President Donald Trump wasn’t invited — he should not have been — because he was judged to be opposed to the NAACP’s civil rights agenda. Housing has long been part of that agenda.

The Boston branch is to be commended for expanding the approach to affordable housing. The branch should keep its civil rights guard up, though. If more people of color obtain jobs in life sciences or climate tech, that doesn’t necessarily mean they will be paid as well as their white co-workers.

“The State of Black Boston” report issued by the Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts in 2010 included a disturbing study done by James Jennings, a Tufts University professor emeritus, that showed income disparities between Black and white workers actually grew larger as they acquired more education, up to the master’s degree level. That’s something the Boston NAACP needs to keep an eye on and assess as it works to help more Boston residents of color afford market-rate housing.

Ronald Mitchell

Editor and Publisher, Bay State Banner

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.